Summer Reading: Photobooks

Originally published July 31, 2020

In this image saturated-era, where we compulsively scroll through streams of pictures chosen by algorithms without visual or contextual logic, the physical photobook is a welcome respite. Displaying images much larger than a handheld device, the tactile experience of a carefully sequenced and edited series of photographs invites the viewer to dwell on each picture or arrangement of pictures, to look closely and see more deeply.

Starting about a decade ago, I took a strong interest in studying photography. While I have always taken pictures using a camera, and even considered pursuing photography over graphic design while at art school, I was at best a talented hobbyist. However, after working as an editorial art director and de facto photo editor while at Climbing magazine, I became intent on seriously studying the craft of photography.

Over the next several years, I took a series of continuing education courses at the International Center of Photography (ICP). It was at ICP that I took a course with Joseph Rodriguez, a documentary photographer whose work on the margins of society—with gang members, sex workers, and victims of both natural disaster and societal indifference, would lead to a long friendship, and close working relationship. Joe and I have now collaborated on several projects, including a photo-film and a book of photographs he took while working as a New York City cab driver in the early 1980s, to be published by powerHouse Books in the fall of 2020.

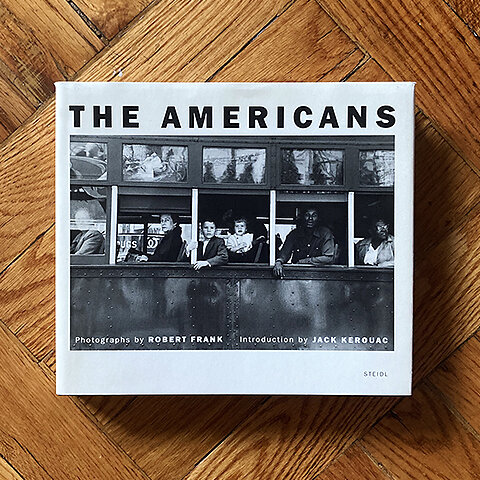

One important thing I learned from Joe is the value to the developing photographer of studying photobooks. These collections of images, carefully chosen, sequenced, and arranged, are a vital asset in learning from great photographers. In the years since, I have amassed a sizeable collection of photobooks, ranging from Robert Frank’s classic The Americans to the massive Magnum Contact Sheets collection. Typically, upon purchasing a new photobook, I will closely study its images, “reading” the pictures, but rarely spending the time to ingest the text, which may range from a few pages of the Forward to extended essays and scholarly texts. This week, I have returned to many of the books in my collection to read the writing, and reflect on how it influences my perception and understanding of the visuals.

John Gutmann: The Photographer at Work by Sally Stein (Center for Creative Photography/Yale University Press, 2009)

John Gutmann was a German Jew who fled the rise of the Nazis by shrewdly presenting himself to a German press photo agency as a photographer willing to work overseas, specifically in the United States. Never mind that he had very little experience in photography, and had certainly never done it professionally.

Settling in San Francisco in 1933, Gutmann set about exploring his adopted city with the camera, making a range of street and reportage photographs. His pictures have a foreigner’s sense of wonder, taking notice of the strange and idiosyncratic details one sees when one settles in a new place, but that native residents may overlook as routine—or, in the case of a deer’s head placed in a public trashcan, undesirable. Gutmann, not a native English speaker, was also drawn to photograph traces of written language such as advertising and graffiti, that add meaning to public space.

Trained as an artist during the German Weimar period, Gutmann’s photographic sensibility and approach to visual composition is quite formalist. His use of unexpected angles, strong diagonals, and symbolism evoke Rodchenko or Lissitsky. This aesthetic is in strong contrast to his American contemporaries, who often composed photographs in a more traditional “straight photography” style. Indeed, the principal photographic group in San Francisco at the time was f64, founded by Ansel Adams, which stressed a formal approach and extreme sharpness in landscape photography.

Having grown up across the bay from San Francisco, Gutmann’s photos speak to me personally. I know these places, and the culture that was born there. As a photographer, they reinforce that a graphic approach to composition, which is my own inclination, is applicable to a wide range of subjects, not just architecture or abstraction.

Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project edited by Sam Stephenson (Lyndhurst/Norton 2001)

Eugene Smith was a giant of American photojournalism. During the heyday of Life magazine, his photo essays including “The Country Doctor” and “The Nurse Midwife” were trailblazing feats of visual storytelling. He was also a difficult, driven man, plagued by internal struggles based in family strife and wartime trauma. He relentlessly fought his editors for control of his work and how it was displayed.

Following his acrimonious departure from Life in 1954, Smith embarked on a sweeping project to document the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Originally contracted to produce 100 images to be used in a book commemorating the 200th anniversary of this industrial center, Smith transformed the project into a sprawling effort to create a visual magnum opus on the scale of a James Joyce novel, or the Odyssey. Working over three years, Smith created more than 17,000 images, of which 156 are published in this book.

Smith attempted to make a singular, layered portrait of Pittsburgh portraying a wide range of people, industry, and civic life. The resulting images are not celebratory, as the client intended, but somber. Dream Street presents a melancholy vision of the city. In deeply contrasted images, Smith shows steel mills worked by sweat-covered men, smoke spewing into the night sky, committees of well-fed businessmen making decisions out of self-interest, and children playing on cracked sidewalks without joy. Though there is deep emotion in these pictures, there are very few smiles.

In the end, Smith—one of the greatest American photojournalists, and the master of the photo essay—declared his Pittsburgh project a failure. It was only published once, as an 88-image essay in Popular Photography’s Photo Annual of 1959. While he may not have succeeded in creating the epic photo essay he initially set out to, this posthumous collection is nonetheless a testament to the power of his singular vision, and of his images.

Endurance: Down and Dirty Offroad Racing by Theresa Ortolani (powerHouse, 2009)

Much of my early life was spent in pursuit of the adrenalin rush of action sports. First as a BMX racer, and later as a semi-professional rock climber. Later, I spent several years as the Art Director of a group of outdoor enthusiast magazines, including Climbing and Urban Climber, where I was able to meld my zeal for adventure with my design career. One of my favorite parts of that job was acting as the de facto photo editor, reviewing and making decisions about the images which would appear in the magazines, and how they would be used. I looked for photos of action which quickened the pulse, while telling the story.

The images in Endurance, by Theresa Ortolani have this same effect. Ortolani followed off-road motocross competitors on the racing circuit. She documents the action of the sport through pictures of blurred motorcycles hurtling through wooded racecourses, kicking up “rooster tails” of mud. Additionally, many of the photos in this book are of portraits, landscapes, details—the people, the gear, and drudgery of a life on the road. Having spent days crossing the western United States quests for stone, I can identify with the monotony of a double yellow down a lonely highway at night in pursuit of a dream.

A Time Before Crack by Jamel Shabazz (powerHouse Books, 2005)

On the surface, this collection of street portraits taken in the first half of the 1980s celebrates the pioneering hip-hop street style of young people in New York City—Puma Clyde sneakers with fat laces, nameplate belt buckles, Lee jeans, girls with door knocker earrings. But if you step back and consider these images more broadly, they are a celebration of Blackness. Shabazz’s youthful subjects enthusiastically present themselves to camera, arms draped around one another, eyes bright, smiles wide. Even the hard rocks—if you can identify them—face the camera proudly and without malice.

The images are rich with subculture signifiers indicative of youth culture in NYC: b-boy crews, around-the-way-girls, couples in matching outfits. A common thread through the images is the influence of the 5 Percent Nation of Gods and Earths, a Black Muslim group that was prominent amongst Black youth at the time, and had a strong bearing on the ideologies of rappers such as Rakim and the Wu Tang Clan.

Made in a period of relative calm, before the plague of crack cocaine decimated inner cities across America, the images in this book not only show what was, but suggest what might have been. In that context, it becomes not just a celebration, but a bit of a lamentation.

The Americans by Robert Frank (Steidl, 2012; first ed. 1958)

There is not much I can say about this book that has not been said previously. The Americans is one of the most important photobooks of the Twentieth century. In the mid-1950s, Frank, a Swiss emigré, peeled back layers of the American onion, beneath the post-war ideal and conformity, to reveal the tension, alienation and discontent beneath. To his outsider’s vision, Americans are a pensive bunch, in a land verging on dystopia.

Jukeboxes in honkey tonks provide a visual soundtrack. Automobiles and their roads dominate the landscape. The photographs are dark and “imperfect”, which fits the point of view perfectly.

The Americans is a long visual poem, a photographic analog to Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, or Alan Ginsberg’s Howl. To add to its Beat cred, Kerouac wrote the introduction.

An Uncertain Grace by Sebastio Salgado (Aperture, 1990)

A preeminent practitioner of “concerned photography”, Salgado asks us to look closely at the “Other.” Originally trained as an economist, his long-term projects examine people subject to circumstances and conditions beyond their control. He works primarily in the global south, in what was formerly referred to as the “third world.” Not a content being a journalist who arrives, shoots, and leaves, Salgado spends long periods of time with his subjects, examining the root causes of their condition, and uses photography as a means to create acute awareness, as he did with famine in the Sahel region of Africa during the 1980s.

This catalog consists of images excerpted from four larger projects and themes: Workers: The End of Manual Labor, “Diverse Images” (with images taken from many projects), Famine in the Sahel, and Other Americas. Opening with images of a gold mine in Brazil where miners clad only in shorts manually transport bags of gold-bearing mud up ladders like ants, these four stories or sections are a virtuoso performance of image making. Salgado is masterful at finding the spark of human dignity, even in scenes of extreme deprivation. Combined with a metaphysical sensibility of magical realism, the vision of humanity in his photos is riveting.

For all my praises, however, this book left me deeply unsettled, wrestling with a conundrum: how does one ingest and respond to beautiful images of people in horrible situations? Starving children, no matter how dignified the manner in which they are portrayed, are still a horrible thing to behold. As a prolific consumer of images, I wrestle with this. And no, I don’t have the answer—but I can’t look away. The pictures won’t let me.

Out of the Corner of My Eye by Sylvia Plachy (Umbrage Editions, 2008)

This catalog, published in conjunction with an in Madrid, is a survey of Sylvia Plachy’s distinguished career. Plachy’s photographic vision is suggestive and impressionist. Her photos float on the edge of the subconscious, mysterious fragments of life posing open-ended stories to the viewer, and asking that we complete the sentence. Most of the photos in this book would be classified as “street” photos, which lend themselves to ambiguity, but even portraits of the famous are treated with this unguarded brush.

The editing of this book is visual poetry. Pairs of images on each spread vibrate with each other, perhaps with a visual rhyme, or a metaphysical resonance that stirs something deep in the subconscious. As a designer who strongly believes in printing spreads at small scale to look at composition and consequence, I appreciate that small versions of each spread are reproduced in the back of the book. While ostensibly serving the purpose of captioning, they provide an opportunity to view the images at thumbnail size, allowing the viewer to find relationships between pictures without getting lost in details.

Spanish Harlem: El Barrio in the ’80s by Joseph Rodriguez (powerHouse Books, 2017)

As I mentioned above, Joseph Rodriguez is a close friend and collaborator. Now that we have gotten this disclosure out of the way, I want to talk about his work. Rodriguez treats the most difficult of subjects, and the most marginalized of peoples, with great empathy, care and respect. He works projects for years, giving the commitment of time, patience and respect to his subjects. This trait is often (and unfortunately) uncommon in today’s visual culture.

Spanish Harlem, an expanded republishing of an edition published in 1994, is an unflinching, but sensitive look at life in El Barrio, a predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood in Manhattan sandwiched between the tony Upper East Side and Harlem. In these pictures, its residents make a life in tenement buildings and hardscrabble streets. They are poor, but proud. A vibrant community celebrates Puerto Rican culture and heritage. Families cling together with love, struggling toward a sense of stability in the face of daunting obstacles.

At the time Rodriguez was making these images, crack and heroin addiction was ravaging America’s inner cities, and Spanish Harlem was ground zero. While he does not sensationalize the ravages of addiction, he does not look away, either. He looks closer. His gaze is human and loving; tender, for these are his people, and at times tough, as he photographs the drug trade and its effects on the community. There are pictures of drug deals and users; one searing image shows an adult’s outstretched hands displaying bindles of heroin and a syringe while a child waits in the background, but these pictures are in the minority. More prevalent are portraits of families and children, persevering through in the face of deep systemic challenges. While the circumstances are trying, they still wear smiles, for they are still children.